Invisible walls are the hardest to bring down

Ephesians 2:13-22

Christ has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility.

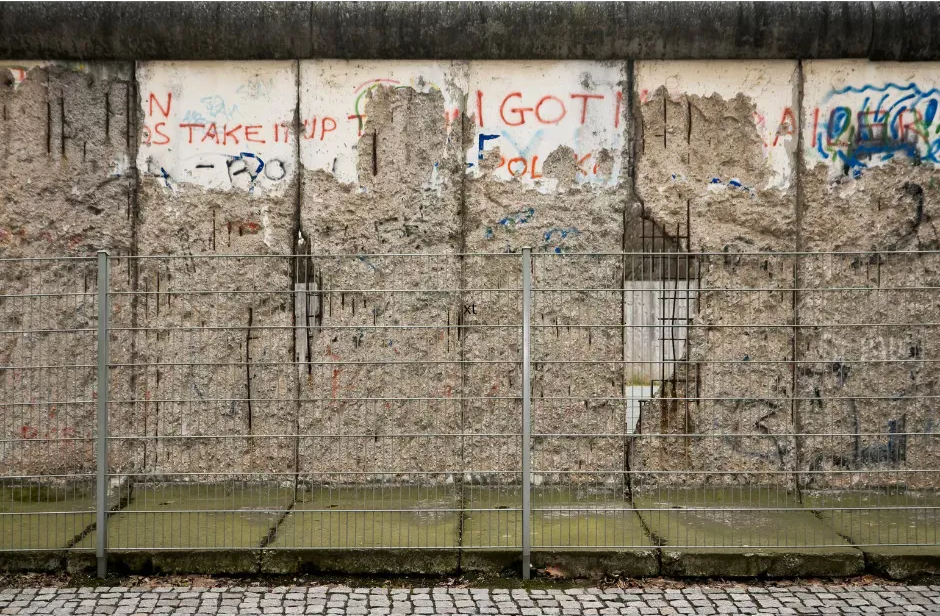

Some walls are so large and visible you can't miss them. You can see the Great Wall of China from orbit. Walls of razor wire surround prison complexes. If you drive from Seal Harbor to Bar Harbor, Maine, stone and brick walls separate the super wealthy from the visiting tourists. Whether inside or outside these walls, you know where you stand, and you don't have to see people who belong on the other side of the wall. Complete separation is the point. Other walls are invisible attitudes and norms that separate us from each other. These walls are more challenging to navigate because they are real, even if you can't see them.

Paul’s letter the Ephesians addresses the divisions between Jew and Gentile in the early Jesus movement. The author likely based this image on the Soreg Wall that divided the inner courts of the Jerusalem Temple, where Gentiles were not permitted. The wall was just over four feet high, so you could see over it and know who was in and out; you could glimpse the inner court but not be allowed in. At the entrances to the inner court were signs in Greek and Latin warning Gentiles to keep out. One stone inscription found by archeologists said,

No Gentile is to go beyond the balustrade and the plaza of the temple zone. Whoever is caught doing so will have himself to blame for his death, which will follow."

You can look, but don't enter on pain of death!

The Apostle Paul writes to the Ephesians about how the invisible cultural walls between Jew and Gentile Christians can be hostile and contrary to the love of God. According to Acts, Paul spent three years in Ephesus, welcoming everyone into the way of Christ, which was still considered a Jewish faith at that time. Welcoming everyone sounds like a nice and polite thing to do, but this was a radical act fraught with cultural conflict. Should the Gentiles keep kosher and follow the dietary restrictions of Leviticus, or do they have to be circumcised when they convert?

The dividing walls of hostility are the cultural norms, traditions, and social identities that create boundaries between who is in and who is out. We cannot visibly see prejudice or ideology, but someone will let us know if we get on the wrong side of the wall. Excuse me, you are in my pew. Oh, I didn't see the wall, but now I know this isn't where I can sit. Sometimes, it is just the subtle stare-down that makes you feel uncomfortable. The black and Latino students in seminary talked about which stores the clerks would follow them to ensure they wouldn't steal anything. If you are an insider, you don't notice the walls because they seem normal. But if you are an outsider, you don't know where to step, and every interaction feels fraught. You don't feel free to be yourself because you are the problem and the one for whom the walls were designed to control.

I learned to build invisible walls when I was a mime. The summer before my senior year of college, I felt I needed to get out and see more of the world. I quit my job as a radio news reporter and joined a traveling ministry of mimes. I knew nothing about mime. On radio, I had been a voice without a face, and now I would be a face without a voice. The first thing I learned was how to build an invisible wall. You may have seen the classic Marcel Marcou act of the walls closing in until he is scrunched into a tight little box. It takes talent to make people believe in an invisible reality. The trick is to move from a curved hand to a rigid flat hand and to hold that point. From the invisible anchor, you can move other parts of your body to make the wall seem solid and real.

One of our best skits was called "The Wall." My partner and I would start dancing in unison with the precision of a drum major on parade. After a half-minute of marching, she would break into disco (it was 1985!). I would come over, admonish her, and call her back to our parade march. She would rejoin me but soon repeat Saturday Night Fever, and eventually, we would get so mad that we built a wall between us. It was hard to make this wall together because we had to create the illusion of the same-sized stone blocks and hold to the same plane of engagement. If one of us was off, the illusion was broken and stopped working. My partner broke the plane once and I pretended to look at the fallen block in dismay, and I picked it back up to restore the illusion.

Act two of this drama focused on what we did on our own sides of the wall. We would go from being angry and waving good riddance to the other side. Then, we would feel regret and approach the wall for a moment before breaking off again. Gradually, we would make it apparent that we both wanted the wall to come down but were afraid to take the first step for fear of rejection.

The grand climax happened when we each reached over the top, touched hands, and methodically and enthusiastically deconstructed the wall brick by brick. You couldn't just pretend the wall no longer existed; it had to be removed in the same fashion it was built for the reconciliation to be authentic. When we hugged, the crowd around us would cheer, applaud, and even cry. We did this skit for youth groups in church basements, Sunday morning worship, city parks, at Jones Beach in New York, and even Chucky Cheese once. Nearly every time, people would come to us afterward and pour out the hurt and divisions they felt with other people. Parents would come in tears with their children. A gay teenager would share that their parents didn't accept them. A multi-racial youth group used the skit as a springboard to discuss how racism affected their group.

I spent the summer shocked at how much hurt and anger existed behind the invisible walls of normalcy. And I was astonished that simply showing how a wall got created and how it could be torn down opened floodgates. I was ill-prepared to handle all the powerful emotions the skit created. I learned to listen, pray with people, and say, "God is good." This skit played a role in my decision to go to seminary. It gave me a vision of what the Apostle Paul meant: Christ brings down the dividing walls of hostility.

Creating a welcome where there has been hostility is no small challenge. Most churches have signs that say everyone is welcome, but we know this isn't necessarily true. Many churches with welcome signs preach an exclusive Gospel every Sunday. How are LGBTQ+ people supposed to know which churches mean what they say, and which ones don't? The statement this congregation adopted in 2012 acknowledges the pain caused by the church in history:

With sadness, we acknowledge that the Christian church has condemned and mistreated persons based on distinctions such as gender, race, gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation. We believe such actions contradict Jesus' call to love one another.

It is a marvelous and strong statement, but you must get through the front door to read it. Given the reputation of the wider church as judgmental and exclusive, many people won’t get that far to know. Being an inclusive and welcoming church requires concrete action, empathy and a willingness to stretch and change. Sometimes people will say, we welcome everyone, but do we have to talk about it?

Mike Fritz said something important to us last week about what it truly means to welcome people. Mike shared with us how painful it was to come home from three tours in Vietnam and be treated like he was a killer. People projected their disagreement with the war on veterans returning home. Mike shared with us how powerful it was to go on the "honor flight" to Washington, DC, and have cheering people meet them at the airport and say, "Welcome home." Welcome home. What made a difference was a specific act of affirmation. The fact that we have Veterans Day and Memorial Day was not sufficient. Mike and many other veterans needed to be specifically and personally seen and welcomed for who he is.

Many people live behind the invisible walls because our culture has shamed them. They might struggle with substance abuse, or depression, recovering from abuse. They might be looked down upon for being a veteran, an immigrant, or they are gay, lesbian or trans. Invisible walls make them feel like they don’t belong. Paul stated it so clearly in Ephesians, that Christ brings down the dividing walls of hostility. We are all made one people by the love of God. Nothing makes me prouder to serve this congregation than the times we say to people, “Welcome home. You belong.”